The Four Stages of Aesthetic Development

Illustrated via the visual art of photography

Page 1 of 1. Version 1.0, ©2011 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

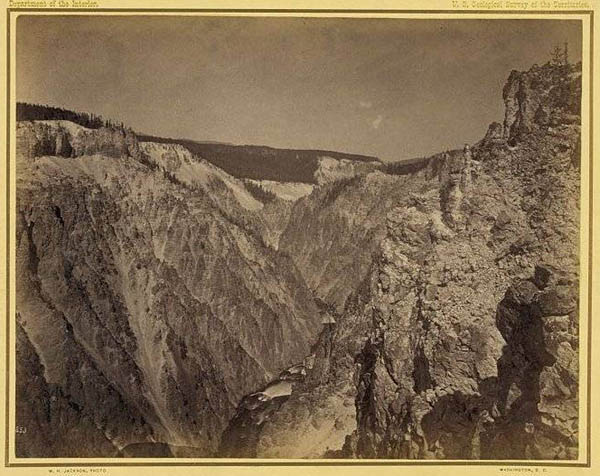

Stage 1. Take the extraordinary and by your handling render it as something thoroughly ordinary:

Fig. 1: Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone by William Henry Jackson, 1800s

Stage 2. Take the extraordinary and by your handling retain its extraordinariness for the viewer to see:

Fig. 2: Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park by Ansel Adams, 1942 or earlier. © The Trustees of the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

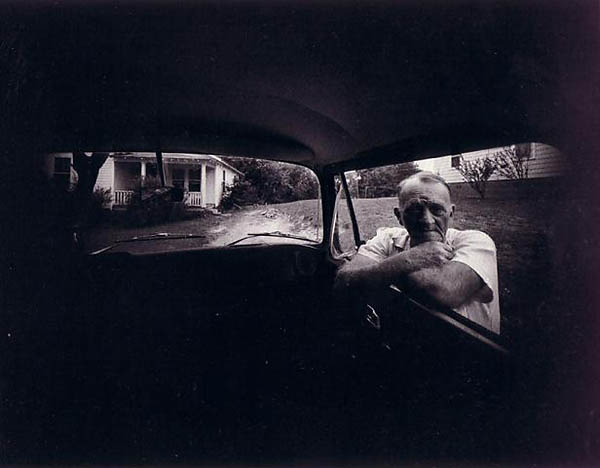

Stage 3. Take the ordinary and by your handling render it as extraordinary:

Fig. 3: Willie Cooper, Danville, Virginia by Emmet Gowin, 1970. © Emmet Gowin

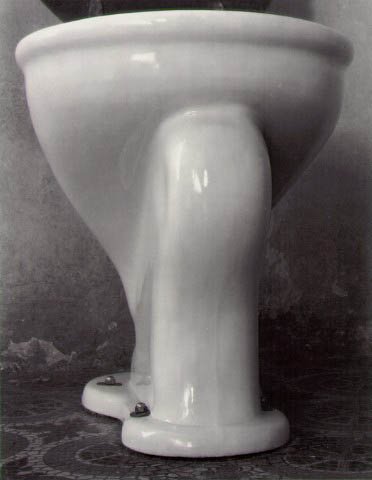

Stage 4. Take the ordinary and by your handling render it as perfectly ordinary ... yet force the viewer to see something extraordinary lurking within that ordinary exterior:

Fig. 4: Excusado by Edward Weston, 1925. © Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents

My apologies to William Henry Jackson re Fig. 1. He did the best that was possible with the equipment available at the time, and was justly famous for having done so. I'd appreciate it if anyone reading this would send me an appropriate picture to replace Fig. 1 with from his/her earliest days with a camera at the Grand Canyon, Eiffel Tower, or similar spectacle.

The above is meant to convey a point, not to be turned into a rigid prescription. For example: an abstract painting might illustrate any level of excellence yet fall within none of the above categories. The main point I'm trying to convey is that great/beautiful pictures don't depend on awesome subject matter. Especially among amateur photographers, there is this persistent misconception that one needs to travel to some spectacular location to create a spectacular photograph.

Later, the same photographer may discover he or she can take a spectacular picture by photographing a less spectacular scene but in spectacular circumstances, such as a local lake at sunset. Occasionally and after years of maturation, a dedicated photographer may finally realize that neither spectacular subject matter nor spectacular circumstances are needed to create excellent art. Unfortunately, at this point he will leave 99% of his audience behind, and any sales/recognition he may formerly have enjoyed will likely plummet.

Strangely, this is a point that doesn't need to be made to even amateur painters. We've all seen someone with a portable easel and paint box busy painting a farmer's field and barn or a quiet pond in mid-morning light. Yet even then, the public is more likely to buy a painting of a snow leopard on a mountainside or Mt Fuji at sunrise.