Shopping for a Landscape Camera

Version 1.3, © 2008 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

All Ansel Adams' JPEGs courtesy of Masters of Photography.

Note, 2012: This article is now four years old and uses a camera that's no longer in production as its main example. No matter: the message that APS-C dSLRs have at least as many strengths as larger cameras for landscape shooting has in no way been obsoleted over the intervening years. I upgraded from the K20D to another APS-C dSLR (Nikon D7000) just last year.

I'm writing this in Jan. 2008 when the newly announced Pentax K20D has got me excited enough to pre-order for the first time. I had been waffling over its predecessor, the 10 mp K10D, since I sold my Pentax DS, but finally decided to wait to check out its replacement first. The K20D is in competition with the also newly-announced Nikon D300 and Canon D40, being semi-pro and mid-sized. It has a currently class-leading 14.6 mp APS-C CMOS imager without bumping up noise at high ISOs (2012: this proved a bit optimistic). It retains and improves upon the K10D's in-body IS, it has a 0.95x pentaprism finder, spot-metering, dust removal, and even adds live view. Price should be about $1300US/Cdn. If the project lead from Pentax had flown to Canada, sat down with me, and wrote down exactly how I'd spec my dream SLR, they couldn't have nailed it any more precisely.

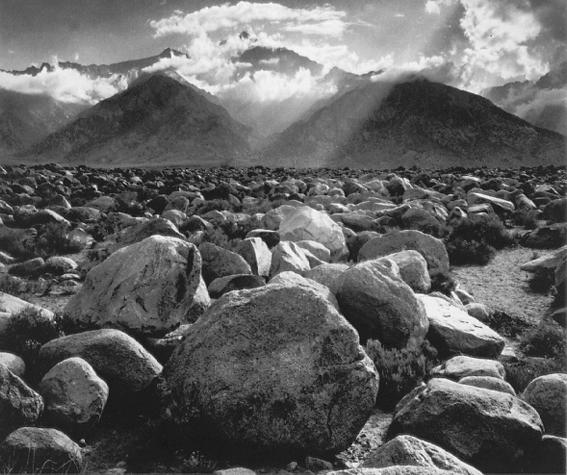

Clearing Winter Storm by Ansel Adams

The affordable high mp count really makes this the ideal landscape camera I desperately wanted five or six years ago. If you're into landscape, as likely as not you're striving to achieve Ansel Adams' pin-sharp detail in 16x20" prints (whether or not his pictures appeal to you). The obvious way to do this is to lug around a large format view camera like Ansel did, but a scanner to do LF film justice costs about as much as a small yacht. Or one can spend the same small yacht bucks on a medium format digital. What may not be clear to someone who dreams of being able to afford the MF digital is...

The DOF dilemma

Mount Williamson - the Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California by Ansel Adams

The law that DOF decreases as focal length increases is simple and remorseless. The normal focal length for the DX format is 28mm, for FF/35mm is 42mm, for 645 is 75mm, for 6x7 is 92mm, and for 4x5 is 162mm. To see how this plays out, consider a typical case. If we focus on a point at 10 feet distance using f/8, we would get the following DOFs (using a 30 micron COC): 28mm = 126 feet, 42mm = 10 feet, 75mm = 2.6 feet, 92mm = 1.7 feet, 162mm = 0.5 feet. If we opt for a smaller aperture, we do increase the DOF, but at the cost of slowing the shutter speed, thus giving subject motion more room to play in. If we decrease the aperture below f/11 we start to lose resolution to diffraction blurring. (Admittedly this can be offset to a limited degree by taking advantage of the Scheimpflug effect if you have swing and tilt movements available to you.)

Resolving power

8 to 12 mp is roughly equivalent to the finest grained film in 35mm format for resolving power (6 or 7 mp if you insist on using 100 ISO slide film). 14 begins to push us into medium format film territory, but as we've just seen, cramming those 14 mp into an APS-C format sensor means we have significantly more DOF than 35mm, let alone MF or LF. This means more of the scene is going to be more in focus with less subject motion or camera vibration blurring. On top of that, you've got grain/noise that doesn't even begin until 800 ISO, and 8 or 9 stops DR.

But if 14 mp is good, then of course 28 would be twice as good, so why stop there? Take a look at the resolution results shown toward the bottom of this page:

Canon EOS-1Ds Mark III Review, page 31

The 21 mp Canon 1DsIII resolves 2700 lp/ph and the 12 mp Nikon D3 resolves 2200. These are both flagship products, so we can be sure their manufacturers spared no effort to achieve the best possible results in every category. That tells us the improvement going from 12 mp to 21 is not the 60% improvement the mp counts suggest, but is only a 17% improvement. This is partly due to the fact that area increases by the square while pixel count increases are linear. However, for the dubious advantage of this 17% gain in res, you've paid the price in a 60% increase in file size with the subsequent overhead in storage requirements and Photoshop slowness. And that 17% res increase is only going to show up at base ISO with tripod, mirror lock-up, etc. As soon as you go handheld and or raise the ISO above 400 or so, kiss it good bye.

Print size

So how large a print does this equate to? Are we now good to go for 16 x 20" with AA (Ansel Adams) grade clarity? As I've explained elsewhere, maximum print size is critically dependent on subject detail. A typical far-subject AA scene like...

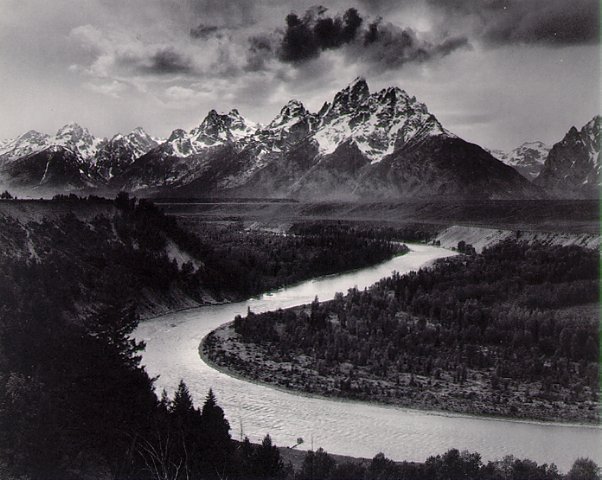

The Tetons and the Snake River by Ansel Adams

...needs a minimum of 240 ppi from the camera. Since the K20D's image size is 3104 x 4672 pixels, that translates into a 13 x 19.5" print, so, no – not quite there. (Similarly for the D300, it's 2848 x 4288 yields a 12 x 18" print at 240 ppi.) But as soon as you move your main interest from the far distance to the mid-ground or foreground...

Up-rezzing note, 2012: An oft-quoted number is that an "average" human eye can resolve 300 pixels per inch. So 240 ppi is more tolerable than optimal. What I do is add a bit of simulated film grain, but only to textured areas of the image, not sky, water, etc. This may seem counter-intuitive at first, but the quasi-randomness of film grain breaks up the regularity inherent in digital pixels and so reduces pixelation.

Tenaya Creek, Dogwood, Rain, Yosemite Valley by Ansel Adams

...(as in Tenaya Creek or Mount Williamson), then dropping to 220 ppi becomes feasible, giving a print size of approx. 14 x 21" – very nearly the same area as 16 x 20" – which fits nicely into a standard 18 x 24" frame.

The sumptuous pixel

Without question digital medium format with its pixel sizes half again as big as dSLR pixels has an undeniable edge in sheer quality. The question for landscape work is of what use is a luxury class pixel if its been blurred by DOF or diffraction? Of course, not every pixel in even the most highly detailed panoramic landscape is given over to detail creation. Areas of sea and sky will always benefit from the subtlety of creamy gradations.

For me, what's more to the point is that if AA and company were able to create masterpieces with such a relatively crude, grainy medium as film, then even dSLR pixels should be more than capable of getting the job done. Photographers as a species tend to be far closer in spirit to technicians and engineers than to painters and poets. If technical perfection were the essence of art, then any competent colour photograph would trump any mere brushwork by a Rembrandt or Vermeer.

In what way is an artist like a pigeon? They both need a bit of grit in their diet. ;)

Low light

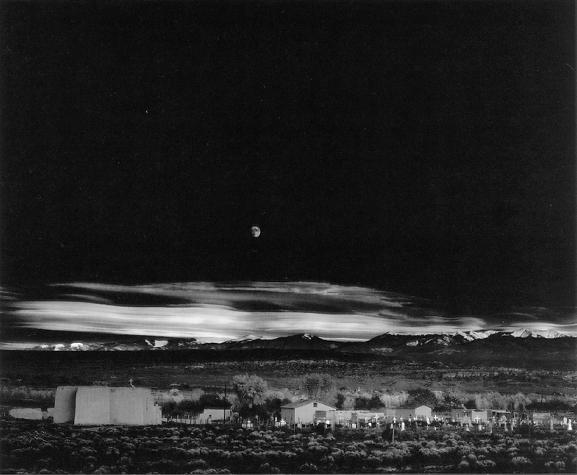

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico by Ansel Adams (1 sec at f/32, 64 ISO)

Taken in 1941, Moonrise, Hernandez, above, quickly became one of AA's defining images. The mostly static subject matter meant that Ansel was free to use any exposure time that was not so long as to introduce moon or cloud motion blur. But most subject matter is not so forgiving. Some combination of high ISO and image stabilization greatly increases both the range of shooting conditions one can work in and the degree to which one can take advantage of the greater freedom of handheld instead of tripod.

The K20D has good, but not stellar, high ISO performance for a modern APS-C sensor camera. A camera like the Nikon D3 or D700 with full frame sensor and sensible megapixel count has hugely better high ISO performance (and consequently wide DR) than the K20D, or any high megapixel count APS-C camera.

Lens options

The purpose of this essay is not to convert anyone into a Pentax user. Nikon and Canon are more than capable of holding their own. But folk wisdom dies hard, and one of its relevant tenets is that only Nikon and Canon among SLR manufacturers have a broad selection of lenses. In fact, Pentax is legendary among the cognoscenti for its selection of superb wide to normal primes, and is rapidly catching up in zooms and long glass. On top of this Pentax is supported by Sigma, Tokina, and Tamron; and that without the occasional mysterious incompatibilities that crop up when using third-party lenses on other body brands. Since I discovered this remarkable resource, Photozone's lens reviews have become my one-source guide to lens shopping. Everything I've read there is spot-on with my own experience.

Getting a move on

The key to lens choice for modern landscape work is that all one really needs is a single good normal zoom – say, 28-70, f/4 – or a couple primes if you lean that way, and the camera body and a few accessories for a complete hiking kit. We're talking about a usable 3 or 4 pound kit, not 4 or 5 times that in weight and bulk – and no tripod needed, thanks to image stabilization.

I sometimes wonder what younger people are coming to without the benefit of a classical education. When I was a child the Walt Disney show was on every Sunday night at seven with a new and awesome one hour production. One such series was called Swamp Fox and retold the story of Francis Marion, who used guerrilla tactics with great effect during the US revolutionary war. This drove home graphically the idea that stealth, savvy, and the mobility of a light kit can trump the heavy artillery. (Of course, Marion was just employing lessons learned from native peoples, and, if memory serves, this was not over-looked in the show.)

It's true that the K20D, like the D300 and D40, is a medium-weight body, so you might be tempted to shave off a pound from it's two pound weight by opting for an entry-level dSLR. But if you're going to forgo a tripod, that extra pound in the body buys you a tremendous amount of inertial resistance to motion, significantly lightening the load on the image stabilization sub-system. Try both and see what works for you.

Galen Rowell, who worked just before digital hit the scene, was perhaps the epitome of a landscape photography Swamp Fox. Routinely back-packing into rugged country, he used to tote the smallest, lightest 35mm camera and lens he could find and shot handheld. Today, he might well have opted for a Nikon D40X with the kit zoom, assuming he could have gotten comfortable with the smaller view in the finder.

Of course, now that such a camera is becoming available I've moved on from landscape to street. The ideal camera for street would be the shell of a pocket cam with the guts of a Nikon D3 inside. No such gadget being currently in existence, the K20D at least has live view, which apparently means one could hold the camera at waist level and pretend to be making some adjustment, while in fact, taking in the back LCD to compose and shoot. It's really too big for inconspicuous street work, but with high ISO and IS it's otherwise just what the doctor ordered.

In sum

There are a few points I hope you'll take away from this analysis. One is that the best tool is not necessarily the most expensive tool. A simplistic take on the question of which digital camera would be the most appropriate for landscape work might suggest that a 39 megapixel MF back would be the best if you can afford it, a 21 mp FF dSLR if you can afford that, etc. But this ignores the much larger DOF inherent in the DX format and also ignores the extra portability of a lighter kit. To extend this line of reasoning, even a compact camera with raw, like the current Panasonic LX2 and the Canon G9, have their own rationales for consideration.

It would be easy to be dismissive of the K20D because its price point – like its other Pentax predecessors – suggests it's not as “serious” a tool as, for example, a Canon 1D or Nikon D3. The smart shopper will recognize a bargain when s/he finds it.

Similarly, even though Canon and soon Nikon have their line-up stratified, such that the D300 and 40D sit in second place in megapixels and in feature counts, it's still up to you to determine which combination of price and capabilities represents the best trade-off for your needs. Opting for the Canon 1DsIII over the 40D, simply because it sports the higher megapixel count and is full frame to boot, ignores the DOF hit of FF and a significant penalty in portability.

We're just ten years into the digital capture era, yet already we're faced with an embarrassment of riches in product choice. And now we're even seeing relatively affordable models that need apologize in no wise as landscape photography tools.

If Ansel were somehow still alive and working today, would he use digital equipment? It's fun to speculate on this. Personally, I feel he would have embraced digital but would have found some way to eliminate the Bayer pattern RGB filter and work directly with greyscale. I believe he would have loved Photoshop and inkjet printing, and would not have hesitated to use Photoshop's local manipulation facilities to achieve control and subtlety beyond even the dodging and burning in the wet darkroom that he was so expert at.