Is Photography Art?

Page 1, version 1.1, © 2009 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

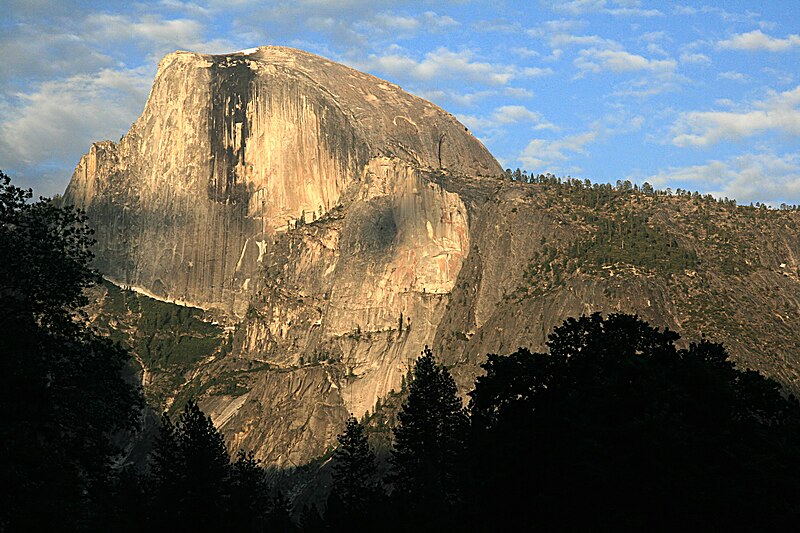

Half Dome at Sunset by Mila Zinkova (source: Wikipedia)

The question occasionally gets asked in photography circles whether photography can be called an art form. Given the relentless experimentation of the past two centuries in the visual arts, the confusion implicit in such a question is more than understandable. If Joe Canonista travels to Yosemite, gets up before dawn, makes the pilgimage to Half Dome by following the well-marked Ansel Adams Trail, puts his ultra-recent-model, ultra-high-megapixel dSLR on his brand-new $1000 carbon fibre tripod, attaches his cherry-picked, spotlessly white-barreled 300mm, f/2.8 prime lens, then uses mirror-lock-up plus a cable release just as the orange-red rays of the rising sun signal the dawn of a new day – is the resulting 16x24 inch Fuji Crystal Archive print a work of art ... or is it not?

Representation vs. expression

Shoe

Not even every sketch is art. If I take pencil to paper to accurately draw the outline of a shoe, I may be attempting a vocabulary lesson for an extraterrestrial or explaining where a repair is needed to the local shopping mall cobbler or copying a new shoe design as an industrial spy ... or I may be creating what I sincerely think of as a work of fine art.

Similarly, in photography we have a fundamental distinction between documentary photographs and art photographs. Many photos are taken with no artistic intent whatsoever; their purpose is solely to document whatever the camera has been pointed at. If I squeeze off a dozen flash-lit photographs of a yellow-tape-cordoned crime scene, I may be a police photographer, a photojournalist, an insurance claimant ... or a self-proclaimed art photographer with a fashionably morbid bent.

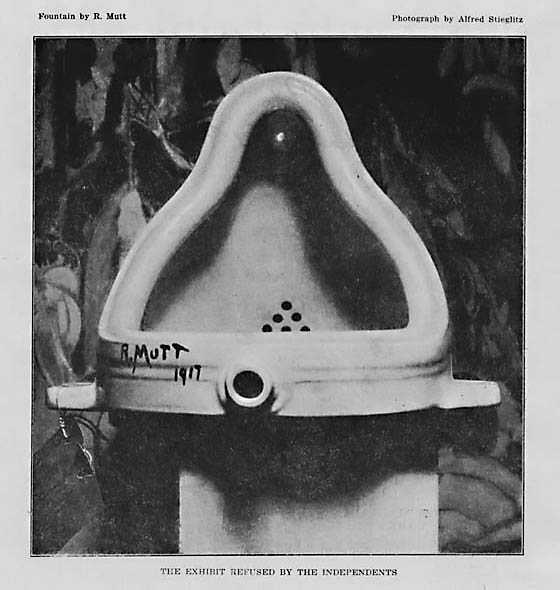

Fountain by Marcel Duchamp, documentary photo of (conceptual) art (source: Wikipedia)

But ultimately, as Joseph Campbell famously quipped: "art is anything you can get away with". Really. That's the only definition that's going to cover everything from the Lascaux cave paintings to Nude Descending a Staircase to the latest post-pseudo-nihilistic-quasi-conceptual visual insult now showing at an art gallery near you.

Yet few people are truly comfortable with the uncertainty implicit in such an open-ended anti-definition, so let's side-step hysteria by turning to history:

Tripping point

Bamboo basket, Bangladore market, 2007 (source: Wikipedia)

Go back to any time in human history preceding 1800 AD, and you'll find the modern distinction between the word "art" and the word "craft" becoming increasingly moot. Visual art was what any crafts-person who worked in a visual medium – whether painting, drawing, etching, sculpture, pottery, leatherwork, stone facade-carving, stained-glass-inlaying, needlepoint, or basket-weaving. – produced. The result landed anywhere on the spectrum from pure utilitarian to pure ornamentation, simply as dictated by the requirement of the job at hand.

Basket of Apples by Paul Cezanne (source www.onlinepaintings.net

Now go forward from 1800 and we see an essential dichotomy emerging between the urban phenomenon of art-for-art's-sake AKA fine art and "mere" utilitarian craftsmanship. Increasingly, it becomes a religious question: didst thou drink the high-grade Kool-Aid or didst thou not? The wedge issue, the foot in the door, from the Impressionist rebellion against the Parisian Salon onward, is whether an object is expressive of an artist's perception or is it not. Until the abstract art movement, a work of fine art presented an element from the external world – what the artist was reacting to – plus an element from the internal world – how the artist reacted to that external element, fusing the result into a single image.