Camera Lenses: a Crash Course

Page 5. Version 1.0, ©2008 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

Apertures

Fig. 9. Aperture & diaphragm (at f/4) vs. pupil & iris

The human eye has a coloured iris that expands or contracts as the level of light brightness increases and decreases. The black "opening" of the eye at the centre of the iris is called the pupil. A camera lens is very similar: there is a diaphragm that expands and contracts much like the iris; and the aperture, which is the opening that light passes through to form an image on the sensor or in the view finder. However, the reason for expanding and contracting the size of the aperture is somewhat different for camera than for eye. We control aperture both to change depth of field (how much of the scene is sharp from closer to the camera to farther away) and as part of the process of controlling how short or long a period of time the picture will be taken within. Apertures are expressed as ratios of the lens focal length. An aperture of f/4 means that the diaphragm is constricted enough to leave an opening (aperture) that has a diameter that is 1/4 of the lens' focal length.

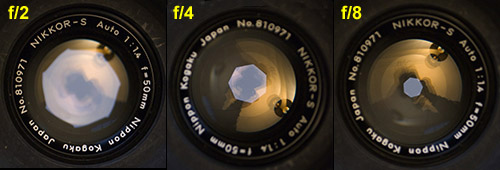

Fig. 10. 50mm prime circa 1970, with diaphragm at f/2, f/4, and f/8

Common aperture settings are f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, and f/64. But every lens has a maximum aperture that the diaphragm can open up to, and f/1.4 is about the widest maximum aperture in commercial use (although occasionally you'll see an f/1.2). This maximum aperture is often called the lens' speed: a wider maximum aperture like f/2 being "faster" than a narrower maximum aperture like f/4. Nearly all lenses have their maximum aperture or apertures marked around the front element, along with the manufacturing company's name and the focal length or focal length range. At the top of the lens circle in Fig. 9 above, we see the maximum aperture is 1:4 (another way of expressing f/4); and the focal range is 17-70mm. In Fig. 10 we see the aperture marked as 1:1.4 and the (single) focal length as f = 50mm.

For technical reasons, the wider the maximum aperture the bigger and heavier the lens will be. Since lenses that go to a longer focal length, such as 200mm, will usually already have a longer barrel, and therefore be bigger and heftier than a shorter lens, such as a 50mm, the speed of lenses tends to be slower for longer focal lengths. So a 400mm prime lens will most likely have a maximum aperture of f/4, while a 35mm prime lens might very well have a maximum of f/2. On top of this, zoom lenses tend to be bigger and heavier than primes (since they have to cover a range of focal lengths), so zooms tend to be "slower" with maximum apertures like f/2.8 and f/4, even when the focal lengths are fairly short. For example, a typical professional zoom lens is the 24-70mm f/2.8. Such a lens will be a relatively modest 5 inches long but weigh 2 lbs (1 kg). This is often paired with the 70-200mm f/2.8, which is 8 inches long and weighs 3 lbs.

An advantage to faster lenses is that they let more light into the view finder, which makes composition and focus easier to perform in low light conditions, such as indoors or at twilight. This is one reason that photographers might favour a faster lens in spite its greater size, weight, and cost. Another reason is that faster lenses let more light reach the sensor when opened to their maximum apertures, making it possible to use a faster shutter speed and therefore to get an unblurred shot in dimmer light. Yet another is that faster lenses mean wider f-numbers mean more depth of field blur, which can be used to isolate the subject and obscure "unimportant" details, as in Fig. 5, above.

As we've seen, the standard APS-C format kit lens is an 18-55mm focal length zoom, but the other two numbers are usually f/3.5-f/5.6. These mean the widest aperture you can get (the lens speed) at the 18mm end is f/3.5 and the widest you can get at the 55mm end is f/5.6. Variable maximum apertures like that are most often seen in budget lenses, while the more expensive professional zoom lenses usually have a constant maximum aperture. Variable maximum apertures allow the designer to keep lens weight down to a minimum, which is a trade-off that's considered more acceptable to amateurs than to professionals. The main advantage today to having a constant maximum aperture is not that it is constant but that it doesn't go to an even smaller aperture at the longer focal length. So an 18-55mm lens with a constant f/4 max aperture means that you're not limited to f/5.6 at the 55mm end. From what I've read, in the past an even more important aspect of the constant aperture was that it simplified calculations you had to perform in your head when doing flash photography and deciding on exposures. Now the computer inside the camera does these things for us, so variable maximum aperture lenses, like f/3.5-f/5.6, are much more common.

Bokeh: Another aspect of apertures and diaphragms is something called bokeh (there's Mike Johnston again, who imported the term from the Japanese and added the odd "h" at the end to insure a two-syllable pronunciation). Bokeh is the on-purpose blurring of parts of a picture resulting from a shallow depth of field, which is achieved by using larger apertures, such as f/2 instead of narrower apertures, such as f/8. The background in hummingbird picture above (Fig.5) is an example of bokeh. The particular feel of the blur derives in some measure from the number of blades in the diaphragm. Bokeh is an advanced topic, but you'll come across the term again and again, so I mention it here.