Quick, Accurate High Contrast Exposures

for Digital Cameras

Page 2. Version 1.3, ©2006 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

The solution

The exposure used for Fig. 3 was not achieved via complex calculations and a $1000 Sekonic 758D handheld digital spot meter. It took about 1 second and used only the features found in any "prosumer"-grade digicam. In this case the camera was a Panasonic LX1. The procedure is simplicity itself:

In non-contrasty light, trust your multi-meter. In contrasty light spot meter the brightest portion of the scene then stop down by X.

(We'll get to X in a moment.) The job of a spot meter is to provide an exposure value that will place the small metered area at middle brightness (so-called middle grey or Zone V from the days of B&W photography). But if the scene is high contrast, we don't want the brightest portion of the scene to be medium-bright. We typically want it as bright as possible just short of becoming a blown highlight. In histogram-speak we want it to snug up to the right edge of the histogram without going past it. The histogram inset in Fig. 3 is a perfect example of what this looks like. Here's a closer look:

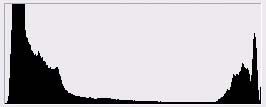

Fig. 5: Typical snug-to-right histogram of contrasty scene

Notice there are values from beginning to end – from 1 to 254 – but no significant spike at either 0 or 255. A spike at either end means there were tonal values in the scene that got smashed down to pure black or pure white in the captured image, like so:

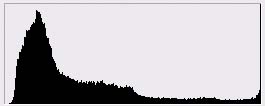

Fig. 6: Histogram with right-hand spike

That thin vertical line at the right edge looks innocuous and can easily be overlooked; but it's all that's left of a wealth of lost detail. Another histogram possiblitity is not so much a spike as a mountain at either end cut in half vertically, like so:

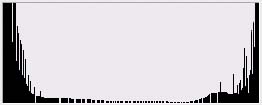

Fig. 7: Twin peaks histogram = scene dynamic range exceeds camera latitude

(The flat central plain in Fig. 7 is not at issue; the central region could take any shape.)

Whether spike at either the 0 or the 255 end, or truncated mountain at both ends, the message is that the dynamic range of the scene has exceeded the abilitity of the camera to record it. The human eye (when combined with the visual cortex) has no such limitation, so a print of a scene clipped by the limited latitude of camera or film stock will look less than realistic to the eye (see Fig. 2). That may be the acme of visual honesty but it is not the illusion of eyeball reality that we have come to attribute to competent photography.

The unaided camera has failed us; the only recourse is to expose right then post process as needed (See Fig. 4).