Dale's Tutorial Tutorial

Version 1.4, © 2008 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

Depressingly, I get compliments on my writing far more frequently than on my pictures. I should probably sell my camera equipment and give up any remaining pretense I may have left of doing visual art. Yet good non-fiction writing is surprisingly easy to do. Here's all it takes:

Never assume knowledge of a fundamental

If you're trying to explain chromatic aberration, you first have to explain refraction and the visible light spectrum (or at least refer the reader to such an explanation via a link), unless you know for certain that your audience will have the requisite background. So first outline your exposition, noting each sub-topic that needs explaining, then check that each concept or term you need to use in those explanations is either assuredly known to your audience or, if not, is explained previously in your document.

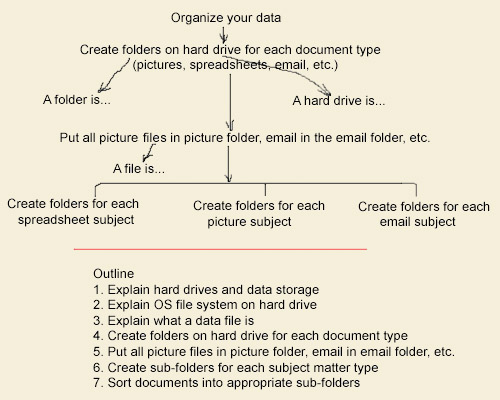

In other words, your thinking would be: "I want to explain X. In order to understand X you need to know W. In order to understand W you need to know V." So first you explain V, then W, then X. That's your outline. If X is something non-trivial, it's usually a bit more complex in that in order to understand X you probably need to understand W1, W2, and W3; and each of those concepts probably have their own precedent concepts, etc. Nevertheless, you end up with a certain number of concepts to explain, and you have to explain them in the order of their basic-ness, and you have to show how each concept leads to the next. Make a crude diagram of that on paper and you've got your outline.

Fig. 1. First jot down ideas as they occur, then put them in explanatory order

The outline becomes the skeleton that the actual words you put on paper serve to flesh out. This tutorial started with four section headings then grew from there. And don't feel straight-jacketed by your initial outline; if you think of a better approach half way into your writing, modify your outline accordingly, then revise to fit.

Tip: Everything in this tutorial applies to business writing, but in addition there are many further considerations when writing business documents, especially as to organization and tone.

Write as if you were talking

You don't need to stare at the keyboard wondering how to phrase a passage. Just imagine yourself explaining the point in conversation with a friend, then type out what you would have said spontaneously in that context. If there's one thing that every human being past the age of three does well it's talking. People practice talking so incessantly, every single day of their lives, that one would think we all have a mortal fear of dysspeekia. Even when writing something highly formal, such as a term paper, write the first draft conversationally – make no attempt to formalize your language – then later go back to formalize as needed. For example: the header to this section started out as "Write like you talk".

Peterborough Greek Festival 3

These pictures have been inserted purely for visual interest; they have no relation to the text.

If your typing is not fast enough or effortless enough to keep up with the flow of your speech, consider using a voice recorder to capture your spontaneous phrasing, then type from the playback, then edit for formalities.

Keep both feet on the ground

The more abstract your topic the more you want to use concrete examples. (I suspect everyone knows this by now, I include it here chiefly for the sake of completeness.) You can explain refraction all you want; as soon as you say refraction is what causes your arm to appear bent when you immerse it in water, your readers will go "ah ha!". You can detail how the visible light spectrum is like an octave but of photon frequencies rather than of musical tones. But as soon as you say that a rainbow is the spectrum made visible, your readers will go "ah ha!".

That said, don't take this to the extreme of avoiding technical language entirely. You do your readers no favours by writing "bending of light waves" each time you are thinking "refraction" as you write. Introduce the word "refraction" with a concrete example, then use it freely thereafter. The next article your readers read, whether on photography or optics or astronomy, may well include the word "refraction" with no explanation and without ever tying it to the phrase "bending of light".