Practical Aesthetics for the Art Photographer:

Meta-Texture

page 1, version 1.1, © 2003 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

OK. The first thing you want to know: is what is this 'meta-texture' business? It's a word I coined to distinguish between the texture of a work of art that comes from the technique of the artist (such as brush strokes or film grain) as opposed to the visual texture of the object itself (such as wood grain or feathers). The next thing you want to know is: why this is of any conceivable importance to you as a photographer? The purpose of the rest of this essay is to convince you that it is.

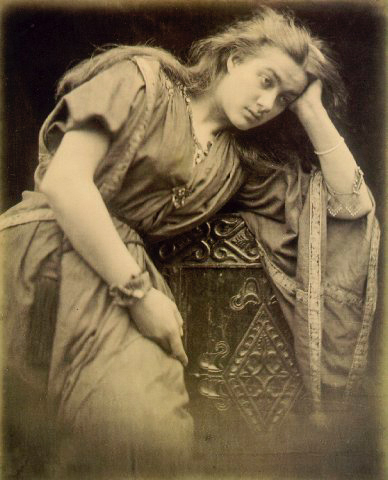

Photography has been with us for the better part of two hundred years. Photography straddles the line between technology and art. A photograph can serve to document before and after for dental work or it can hang in a gallery of fine art. While many serious photographers used the early camera to do art during the 1800s, their work was largely looked down upon as being the poor relation of the "real" art of painting. Such photographers mostly strove to achieve a painterly, or atmospheric, look to their work...

Fig. 1: Mariana by Julia Margaret Cameron (scan courtesy of Masters of Photography)

...or achieved it without striving thanks to serendipitous equipment limitations...

Fig 2. Snapshot, Paris, Alfred Stieglitz (scan courtesy of Masters of Photography)

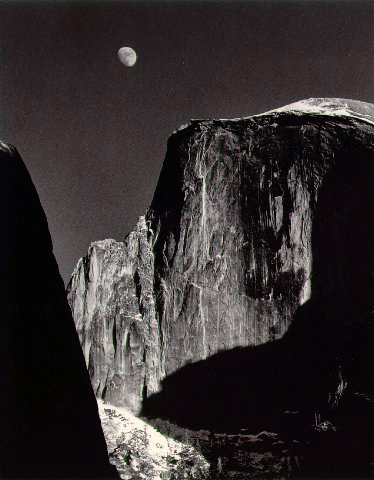

But by early in the 1900s the technology of photography was beginning to mature to the point that repeatable results were possible. Art photographers were beginning to question the idea that photographic art should imitate painted art. This culminated in the Group f/64 Manifesto of 1932:

"The name of this Group is derived from a diaphragm number of the photographic lens. It signifies to a large extent the qualities of clearness and definition of the photographic image which is an important element in the work of members of this Group."

Their simple but powerful idea is that the clarity of detail that is the forte of photography should be the fundamental aesthetic of art photography (just the facts, Ma'am).

Fig 3. Moon and Half Dome, Ansel Adams (scan courtesy of Masters of Photography)

This defined a school of thought that gradually became very dominant in the art of landscape photography. So much so that I suspect the majority of currently practicing landscape photographers have never considered an alternative. A photographer who accepts the f/64 aesthetic gets to choose his time and his place to capture his image, but the painter - even a strict realist - has an added dimension - she gets to choose how she will render the detail of the image. Explanation follows.