Existing Light Exposure Metering

Page 2. Version 2.3, ©2003, 2005, 2009, 2012 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

Grey Power

Any well-supplied photography shop will sell you something called a grey card. This piece of cardboard has one surface that is coloured a very carefully controlled shade of grey. This is a shade of grey that is in theory, at least, exactly half way in exposure between pure white and pure black, as in Fig 2. Now, we might assume from that fact that a grey card therefore reflects exactly 50% of the light that falls on it back to the camera. In fact, the number is 18%, and therein lies a tale.

Technical note: Grey cards actually reflect 12.5% and require a half-stop compensation. 18% is what they're supposed to reflect. Due to a mistake in the instructions that came with the Kodak Grey Card for many years, many people use the grey card incorrectly. See here.

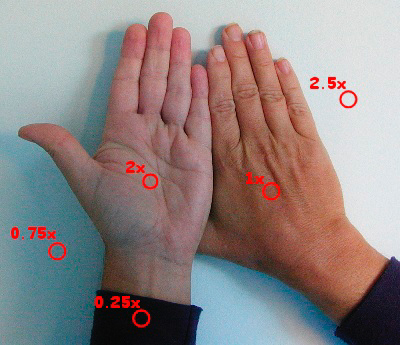

Fig 3. Brightnesses. The palm of my hand is twice as bright as the back of my hand.

In a very real sense the human eye is also a sensor and it also counts photons to determine the relative brightness of an object. One of the rules of thumb used in photography is that the palm of a Caucasian hand is twice as bright as a grey card (non-Caucasians should experiment, but the difference is not great). In the above photo the back of my hand happens to be very close to the brightness of a grey card; the background is very nearly white; and the navy sleeves are very nearly black.

The catch is that, while the palm of my hand happens to reflect twice as many photons as does the back of my hand right next to it, the palm will not appear to be anything near twice as bright to the eye. Let's say that we use a light meter on my palm and get a reading of 1000 candles and a reading on the back of my hand shows 500 candles. This doubling in brightness is called a one stop change (for historical reasons). The entire scene ranges four stops from the left sleeve that is ¼ the brightness of the back of my hand to the pale blue background that is 2½ times the brightness of the back of my hand, and 16 times the brightness of the sleeve. This 16-fold increase in brightness, however, appears as a four-shade (four Zones) change to the eye. And the difference between back of hand and palm is a one-shade difference. The eye compresses brightnesses according to a logarithmic curve, and a print reflects that compression.

If we could all go around taking pictures of grey cards and nothing but grey cards metering would be child's play. Let's examine how this is done in detail; it will form an excellent foundation for metering more complex scenes.

Metering in the Key of Middle Grey

Reciprocity: please take a side trip to pages 4 and 5 of my tutorial Camera Fundamentals if you are not familiar with the principle of reciprocity that operates between apertures and shutter speeds. An exposure of f/11 at 1/125th second is equivalent to an exposure of f/8 at 1/250th second and an exposure of 1/000th at f/4. Each such equivalent combination of aperture and shutter exposes the imager to exactly the same amount of light (assuming an unchanging scene).

The importance of this is that there is some combination of shutter speed, aperture size, and sensor ISO that will perfectly expose a grey card in a given amount of light. This means that the sensor has been activated by receiving as many photons per pixel or film grain or dye cloud as is needed to generate an output that is half-way between the pure white of over-exposure and the pure black of zero-exposure.

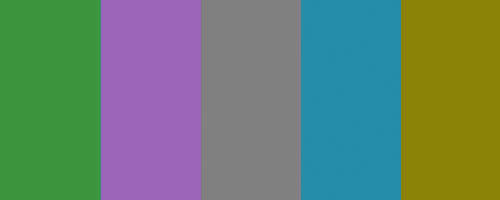

It's important to realize that there is also a shade of green and a shade of blue and a shade of red, etc., that will also perfectly expose the sensor. If you put these colours beside the grey of the grey card they will all reflect 18% of the light and they will all be identical in brightness but different in hue:

Fig 4. These colours would all appear roughly the same if you were completely colour blind

However, the camera measures brightness using a light meter, and light meters "see" the world in shades of grey, just like black & white film (and your own eyes at night). A light meter simply sucks in photons and spits out electrons; it doesn't know from photon frequency AKA colour. To a light meter Fig 4 is all one colour – middle grey.

There are several different light meter variations:

- 1 degree spot meter: this is a handheld meter that reads the brightness of a single spot, no matter how near or distant, that is 1/360th of the horizon in diameter.

- X percent spot meter: these are built in to some cameras and read the brightness of a small area of the image you see when looking through the view finder. These days X is usually between 2 and 3, but even a 1% spot meter covers a broader area (and is therefore less precise) than a 1 degree spot meter except when using a long tele lens.

- Partial spot meter: same as above but reading a larger area, usually the size of the central focusing circle (typically 4.5% up to 9.5% in a Canon camera).

- Centre-weighted averaging meter: either handheld or built-in these read the full frame then average all the different brightnesses into one over-all reading. Typically, the central 60% to 80% of the frame is given as much emphasis as the entire remainder of the frame.

- Incident light meter: handheld meter that surrounds the light sensor with a translucent dome that serves to automatically average the incoming light.

- Evaluative meter: (often called matrix or multi-pattern) this is a computer program built into most modern cameras. The program takes readings from several sensors reading different portions of the frame then evaluates them to attempt to arrive at the optimal exposure setting based on either sophisticated logic or a database of successful exposures.

It would be great if one could program the computer inside a modern camera to take into account everything in this tutorial, and thereby automatically find the correct exposure in every situation. That's what evaluative meters are supposed to do, but unfortunately don't. To evaluate your own evaluative meter, read here.

In the simple case of measuring the light from a grey card filling the entire frame, each of the above meters should arrive at the same recommendation. (Although, technically, an incident meter does not measure the light from an object, but instead measures the light falling on an object.)

Even more important – the crucial point about (non-evaluative) light meters – is that they assume that whatever they are metering is a grey card or grey card equivalent.

Fig 2. Black (0.5% reflectance), middle grey (18% reflectance), white (90% reflectance)

If you point a spot meter at the black region of Fig 2 it will give you a reading that will let in enough light to expose the black region as if it were middle grey (and both the grey region and the white region would then show as pure white). Similarly, if you point a spot meter at the white region of Fig 2 it will give you a reading that will cut down the light reaching the imager to expose the white region as if it were middle grey (and then both the grey region and black region would show as pure black). An averaging meter will do exactly the same thing, but based on the frame as a whole.

This is such an important point that if at all possible you should test this for yourself. Set your camera on spot meter mode (which hopefully it has) or centre-weighted and aperture priority. Find something as close to non-reflective black as possible then fill the frame with that object. Note the suggested shutter speed reading. Now something white that will fill the frame and bring it into the same light as the black object. Note that the suggested shutter speed now reads a much smaller time value than it did for the black object. The light hasn't changed but the suggested exposure has.

As always, our tendency is to assume that our tools understand what they are doing, and as always this tendency will turn around and bite us on our posteriors just as often as we succumb to it.

NON-EVALUATIVE LIGHT METERS ASSUME THEY ARE METERING A MIDDLE GREY TARGET.

Incident meters are a previous attempt to by-pass the middle grey dilemma. They also assume they are metering middle grey, but they are meant to be pointed at the light source (often the sky in existing light photography) instead of the subject.