Lessons in Composition for the Art Photographer

Version 2.3, Page 6, ©2001 by Dale Cotton, all rights reserved.

Lesson 3: Energy and Directed Attention

Painting and photography have in common being two-dimensional: they lack both the third dimension of depth and the fourth dimension of time. Throwing away depth may hinder a literal representation of the world, but as we saw in Starry Night, it is actually a boon to achieving unity in design. Throwing away the fourth dimension, like being paralysed from the waist down, represents a serious handicap - the loss of motion.

In Figure 3a, the illusion of motion is created by the standard photographic technique of motion blur. We have a visceral response to the blurred train engine.

Figure 3b. Blue Car ©2001 by Karen Ball

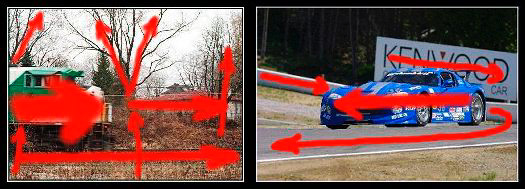

In 3b, on the other hand, it's not immediately obvious whether the car is parked or in motion, yet the image is charged with energy. The portion of the road behind the car and the portion it rests on are both on slants. Viscerally, we know that gravity pulls upon any object on an incline. The tilted Kenwood sign is like a child at the bottom of a teeter-totter: poised for lift-off - more latent energy. The gleaming blue and curvaceous car is fragmented from the rest of the picture - nothing compositional really binds it to the background: more energy.

And energy is the key to the static arts. Look back at Figure 1c, the simple beach scene. Nothing's happening. Nothing catches the eye to draw me into that world. Painting and photography are about the very things they lack: time, motion, and (literal) energy. Look back at Figure 1f, Starry Night. There isn't any hint that literal motion was taking place in front of Vincent's eyes as he painted. Stars, trees, and villages don't go anywhere. Clouds normally move slowly. Yet we saw how the artist charged the image with energy by playing compositional brinkmanship, flirting with fragmentation.

Figure 1f. Lines of attention in Starry Night

An artist plays ju-jitsu with the dynamics of human perception. When I look at Starry Night, my mind cannot take in the entire contents of the scene simultaneously. My focus of attention has to move from region to region of the canvas. When my attention jumps from moon to stars to cypress to village in some order - that's the fourth dimension of motion and energy I have at my disposal as a painter or photographer. When I involve the viewer in the implied motion (Figure 3a) or energy of imbalances (Figure 3b), that's more motion and energy at my disposal.

Beyond unity/fragmentation, beyond rhythm and rhyming, the pattern in which I arrange the shapes within an image has the potential for this third element of energy: the lever and inclined plane.

Figures 3a & 3b. Lines of attention